Institute for Gravitation and the Cosmos

Penn State physicist honored with 2025 Lars Kann-Rasmussen Prize

2025-02-20

Jacob Bourjaily, associate professor of physics, was honored with the Lars Kann-Rasmussen Prize for 2025 by the Niels Bohr International Academy (NBIA), in Copenhagen, Denmark. The prize is awarded annually to an exceptionally talented young individual who has had very high impact in research and has or has had close connections to the Niels Bohr Institute. Bourjaily was presented the prize by Lars Kann-Rasmussen, former chairman of the board of VKR Holding and the Villum Foundation, at an award ceremony on February 24 that was attended by the head of the Niels Bohr Institute Joachim Mathiesen, Deputy Dean of Research Lise Arleth, and NBIA Director Poul Henrik Damgaard. “I am extremely grateful for the generosity and support I was given during the nearly ten years I spent at the Niels Bohr Institute and International Academy,” Bourjaily said. “Through the generosity and support of the Danish people and the Niels Bohr Institute, I was able to build and lead the world’s largest team of postdoctoral scholars studying exciting new developments in quantum field theory. It is a great honor to be awarded this prize for the work that was started there.” Bourjaily was awarded the prize "for his fundamental and original contributions to quantum field theory, guided by an on-going quest for both simplifications and deeper understanding." Bourjaily is a theoretical physicist whose research revolves around quantum field theory — the basic theoretical and mathematical framework that combines quantum mechanics with relativity. He works to revolutionize how quantum field theory is used to make predictions for experiments. Among the most important of these predictions are scattering amplitudes, which encode the predicted relative likelihoods of all possible outcomes of any experiment. Bourjaily’s research has led to great advances in the ability to make such predictions and in understanding the mathematical form that these predictions take.

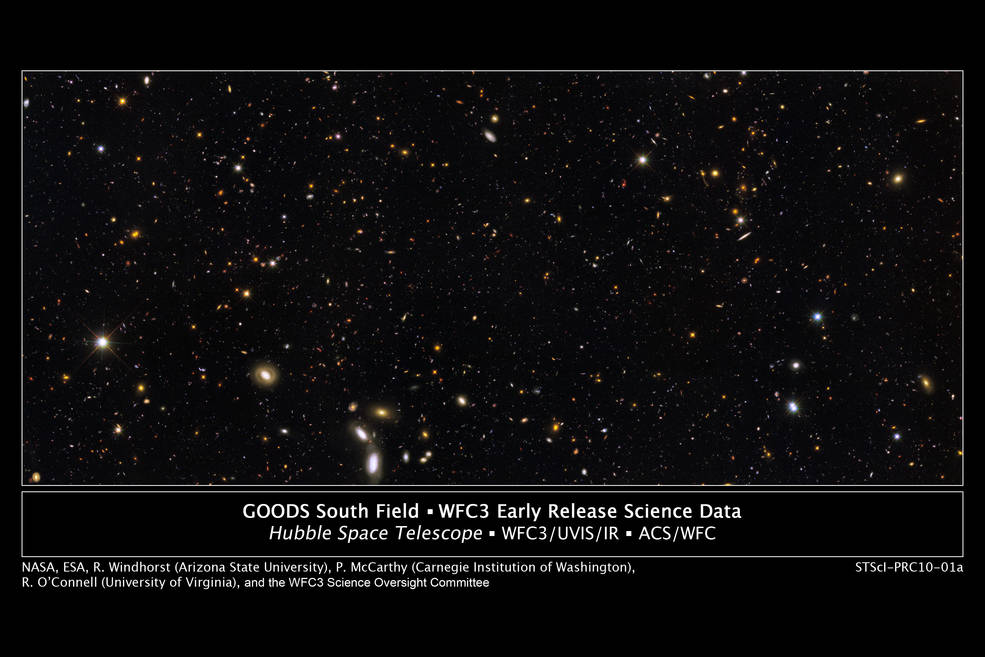

Astroinformatics

Astroinformatics applies data science and machine learning to astrophysics and cosmology. IGC members working in astroinformatics are also affiliated with the Institute for Computational and Data Sciences.

Astrostatistics

Astrostatistics is the study of how to use astronomical observations, with their associated uncertainties, to constrain models of astrophysics and cosmology. Measurements are made with imperfect instruments and the way in which many objects are observed can be biased by something in their local environment, like dust, that reduces or enhances the emitted signal. Accurately inferring the model from the data requires a careful accounting for all those effects. Visit Penn State's Center for Astrostatistics website to find out more about. [Image Credit: NASA/Ames/JPL-Caltech]

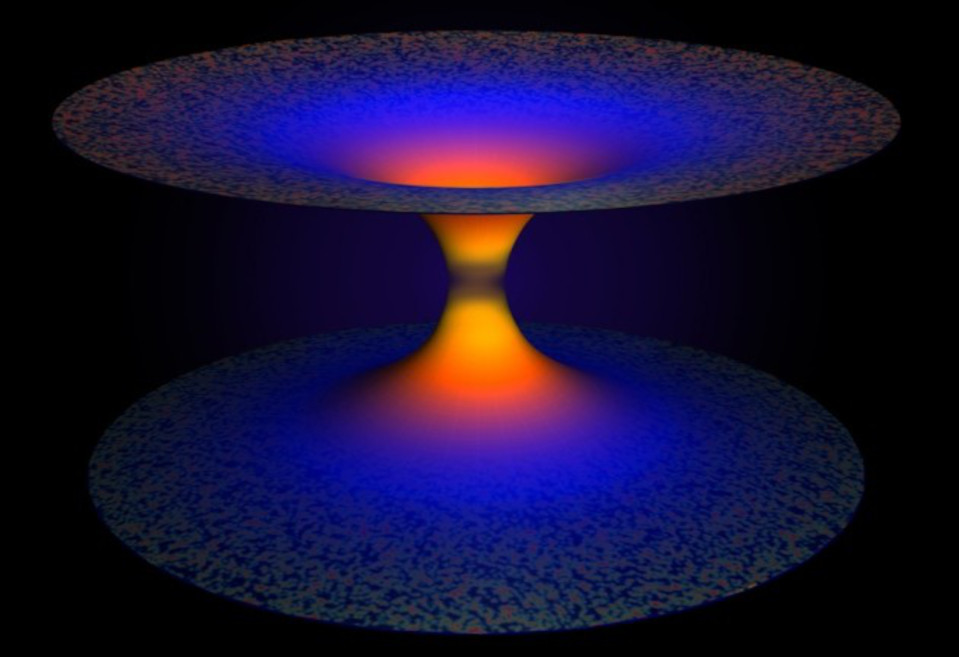

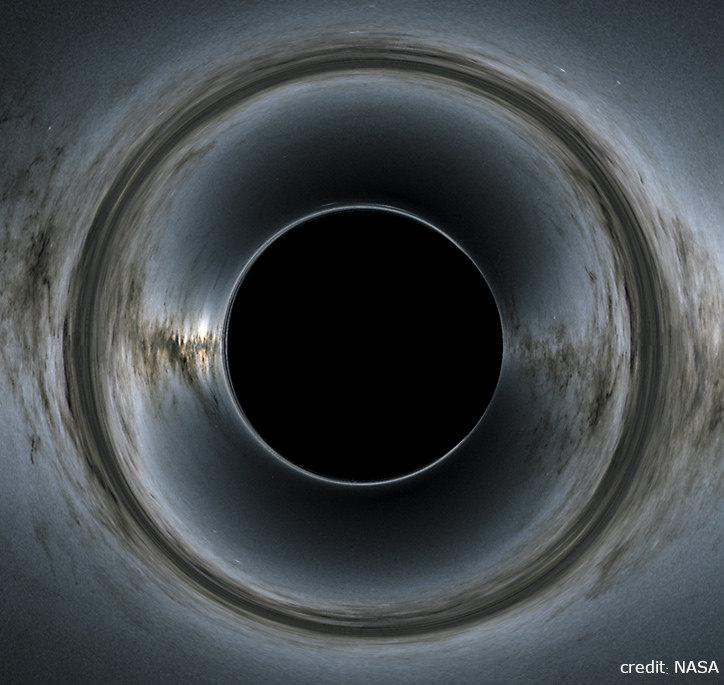

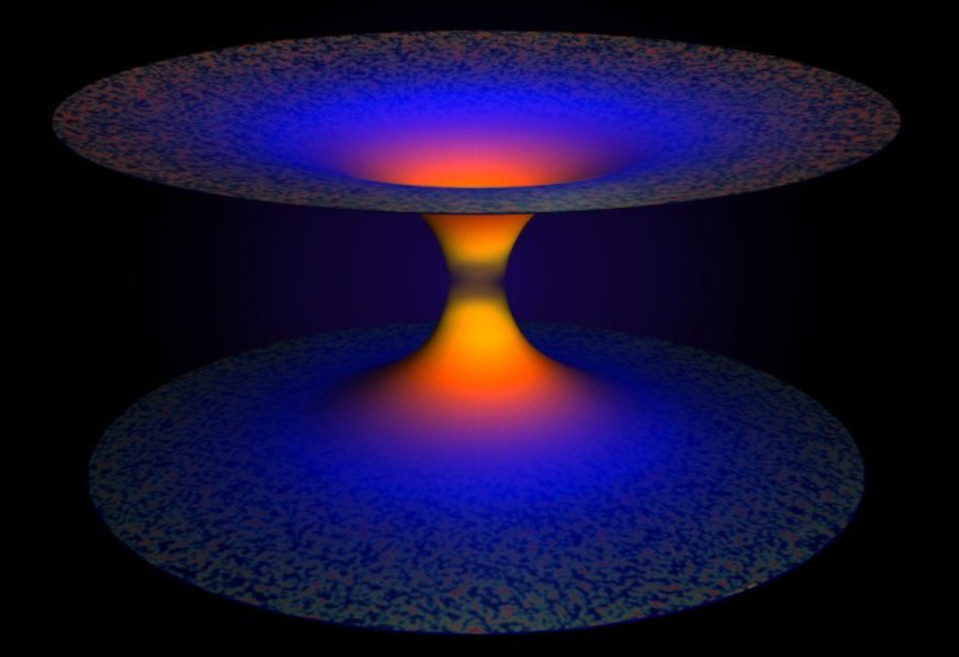

Black Holes

Black holes are regions of spacetime so dense that nothing can escape their gravitational pull - not even light. Researchers at Penn State study black holes theoretically in the context of general relativity and candidate theories for quantum gravity as well as observationally through electromagnetic and gravitational wave surveys.

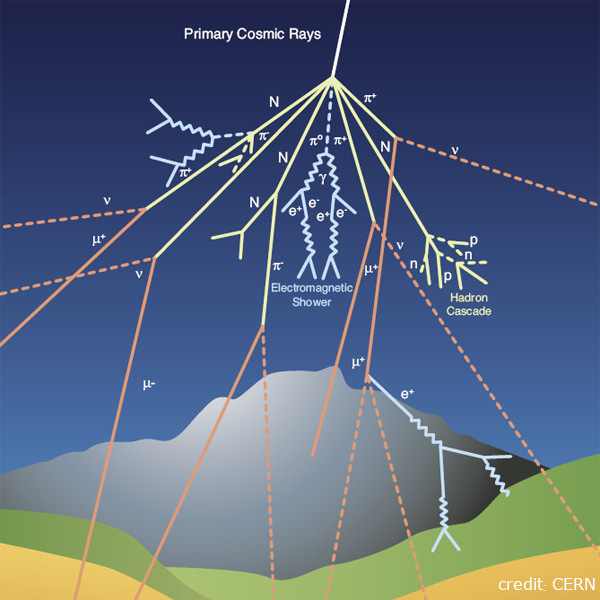

Cosmic Rays

Cosmic Rays are elementary particles and nuclei, detected on or near the Earth, that originate in energetic processes in the universe. Physicists work to characterize the cosmic ray spectrum: the abundance of different types of particles and their energies. Observations of the primary particles are made in space (e.g., the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer, AMS, on the International Space Station) and with high-altitude balloons (e.g., the High Energy Light Isotope eXperiment, HELIX). When cosmic rays interact with the Earth's atmosphere, they generate showers of other particles, called secondary cosmic rays, that are detected by instruments on the ground (e.g., the Pierre Auger surface water tanks and fluorescence detectors), and under the ground (e.g., the AMIGA, Auger Muons and Infill for the Ground Array extension for Pierre Auger). Cosmic ray data is used to constrain models for sources that can produce high-energy particles, either extremely energetic astrophysical environments like those around Active Galactic Nuclei (AGN) or extreme events like gamma ray bursts (GRBs).

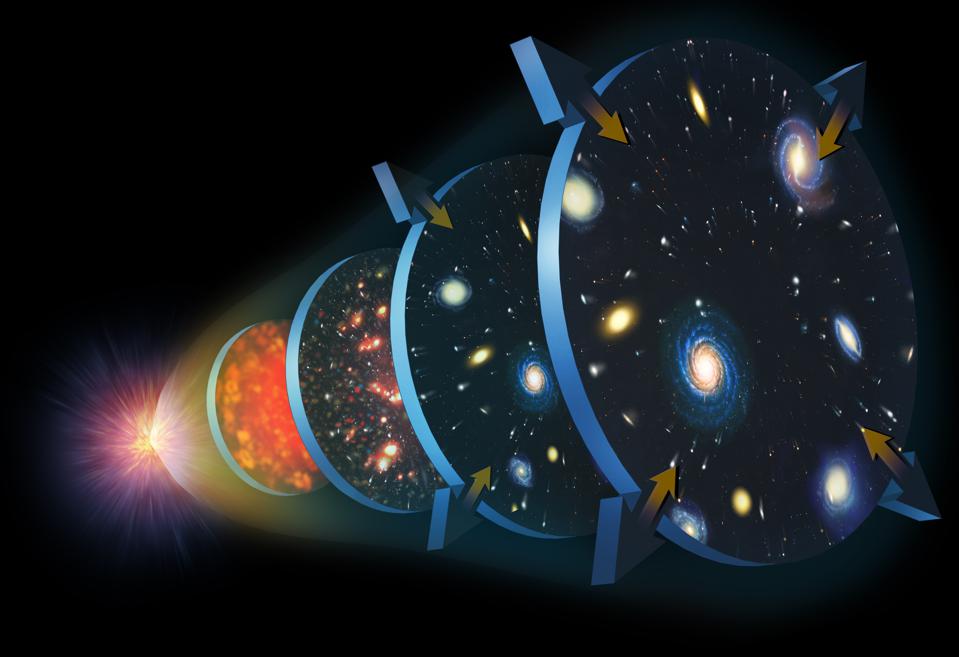

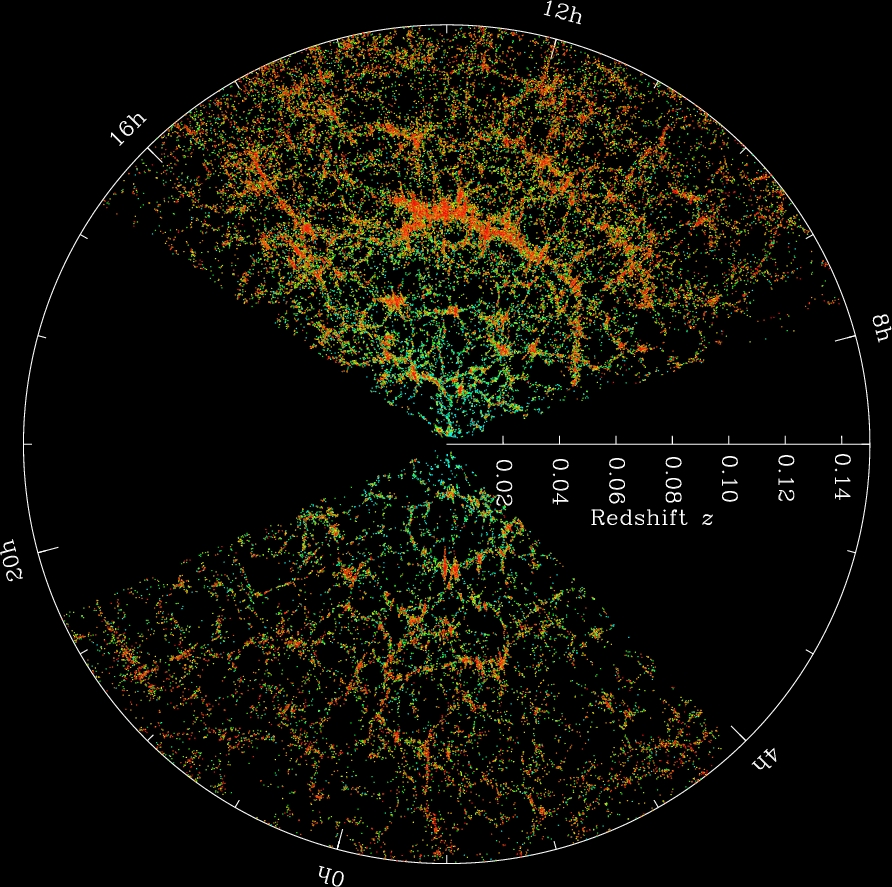

Cosmic Surveys

Cosmological surveys map out the distribution of matter in the universe. Some surveys may target a particular type of object by looking for a very particular spectral signal. For example, the HETDEX survey is designed to find a class of galaxies, Lyman-$\alpha$ emitters, at a time when the universe was about 10-11 billion years younger than it is today. By precisely measuring how those galaxies are receding from us, HETDEX will provide a new constraint on the expansion rate of the universe and the role of dark energy in the past. Other surveys collect light across a wider range of frequencies. For example, the Rubin Observatory Legacy Survey of Space and Time (LSST) will take optical images of a large fraction of the sky, nearly every night. LSST will detect nearly 4 billion galaxies that can be measured so precisely that distortions in galaxy shapes due to gravity can be used, statistically, to map out how both dark and luminous matter are distributed in the Universe. Because LSST will image the same part of the sky so often, it will also capture the variations of light emitted by objects that are changing rapidly, allowing studies of the dynamic universe.

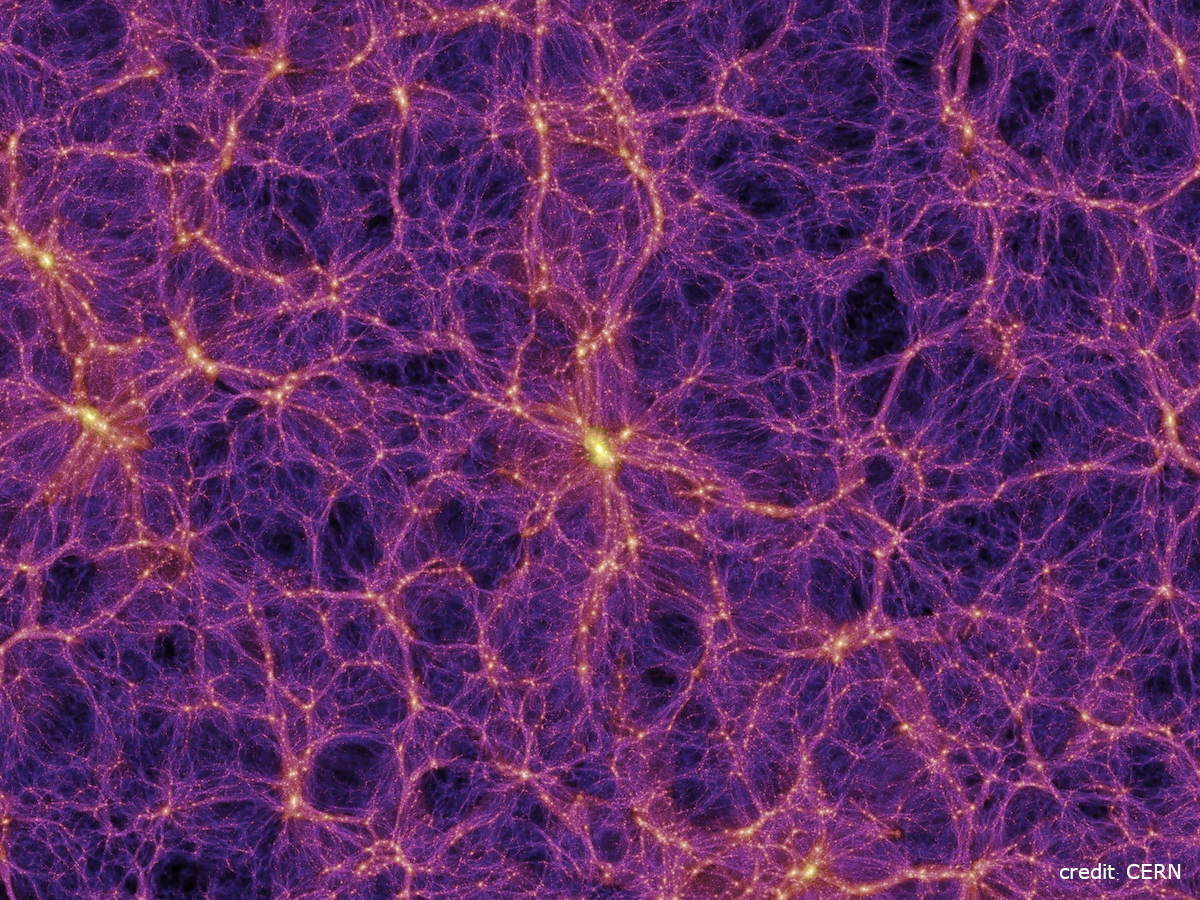

Dark Matter

Matter can be detected by its gravitational pull. Many different observations together indicate that about 84% of the gravitating matter in the universe emits no detectable photons. This is the dark matter, and the quest to understand what it is drives the work of large communities in cosmology and particle physics. Experiments like the Large Underground Xenon experiment, LUX, are designed to search for possible interactions between dark matter particles and the particles of the Standard Model. Surveys like the Rubin Observatory Legacy Survey of Space and Time, LSST, will carefully map out the distribution of dark matter, probing for signs that some particle physics interactions was at work along with gravity and affected the evolution of structure. Gravitational wave observations may also reveal something about the nature of dark matter if, for example, the population of detected black holes is inconsistent with the expected astrophysical population.

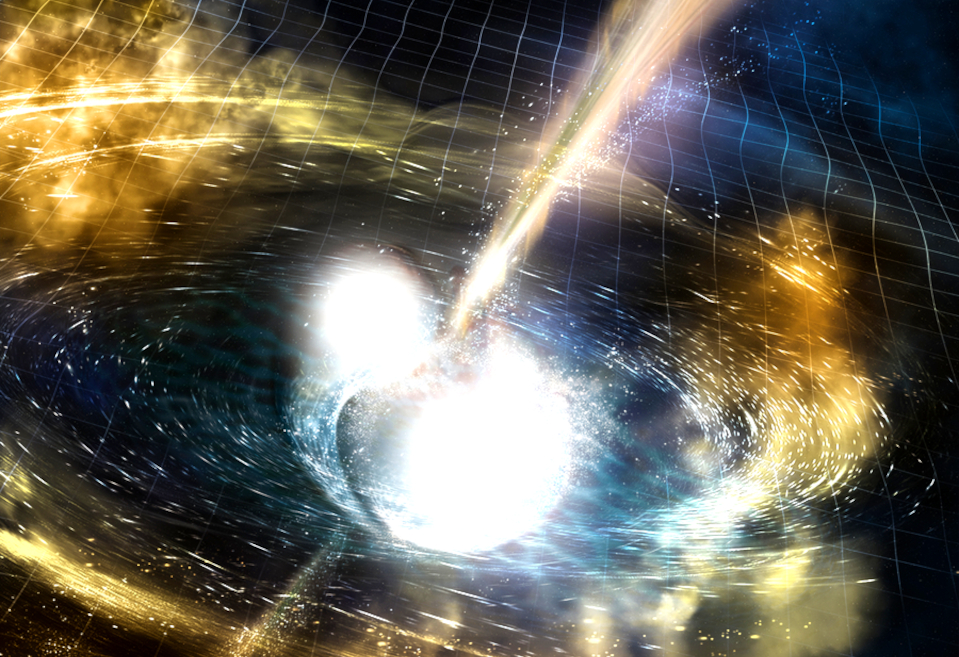

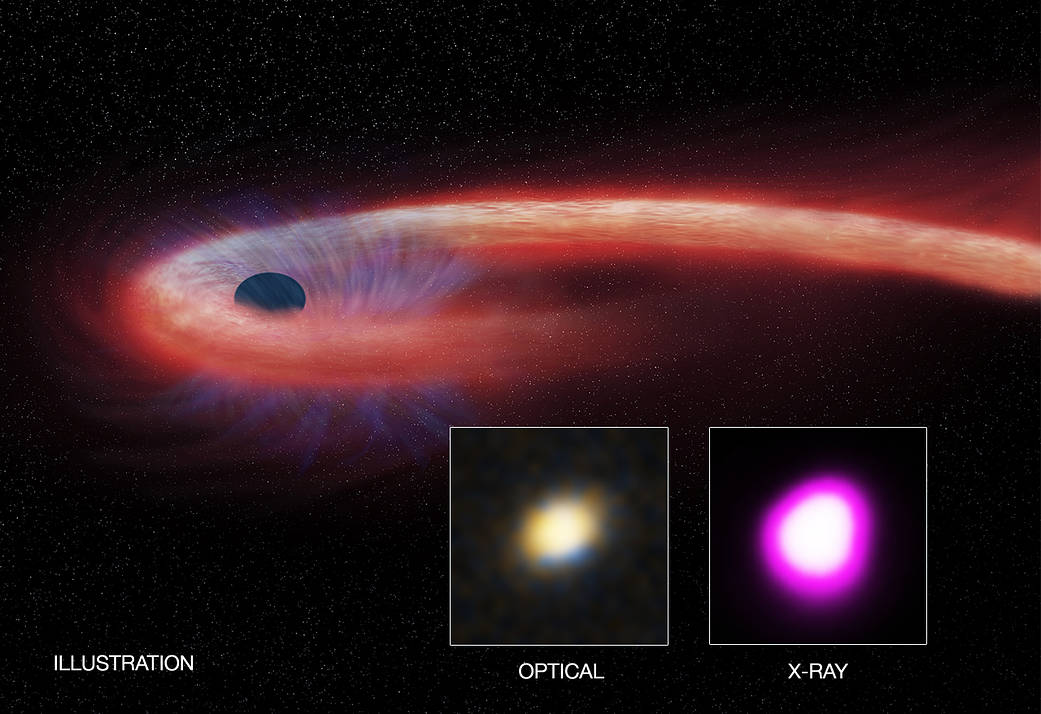

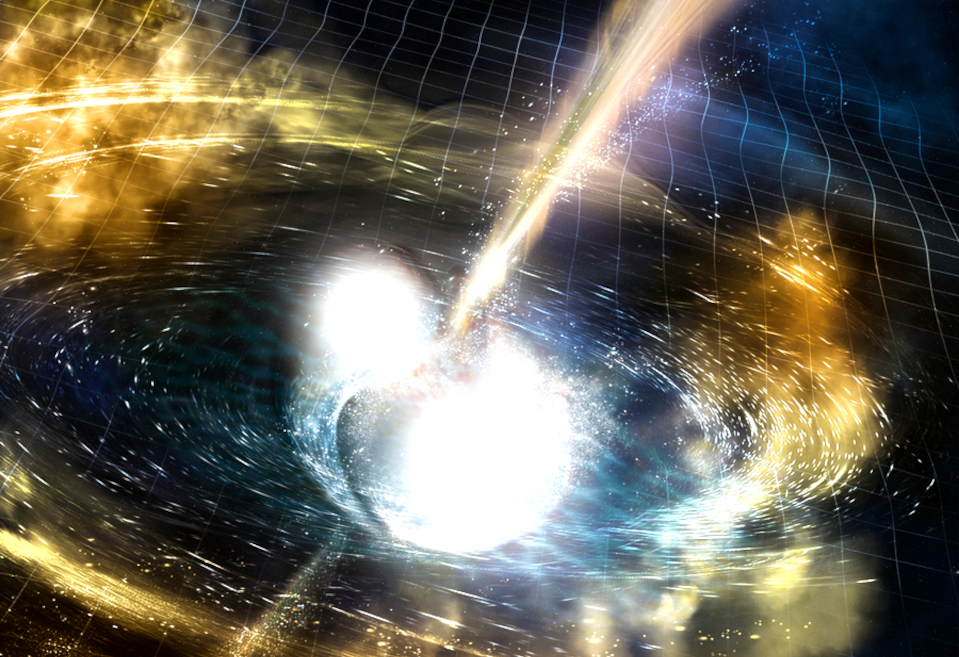

The dynamic universe

Many dynamic phenomena in the universe occur over a period of seconds to years. Events with quickly evolving signals include the explosions of Type 1a supernovae, the destruction of stars passing too close to a black hole, and the merger of neutron stars. Some transient phenomena, like Type Ia supernovae, release light in such a reliable way that they can be used as standard reference events to study the evolution of the universe. Other events provide information about matter in extreme environments and at very high energies. These phenomena may be observed not just through their electromagnetic emission, but also through the generation of particles or gravitational waves. For example, a merger of two neutron stars first detected as a gravitational wave event, GW170817, was subsequently observed across the electromagnetic spectrum. Fluctuations in the energetic matter streaming out from the vicinity of a black hole in the center of a galaxy, the flaring blazar TXS 0506+056, produced both neutrinos detected by IceCube and high-energy gamma rays. Several new instruments promise to bring an explosion of data for the study of transient phenomena in the universe. [Image Credit: Illustration: CXC/M. Weiss; X-ray: NASA/CXC/UNH/D. Lin et al, Optical: CFHT. ]

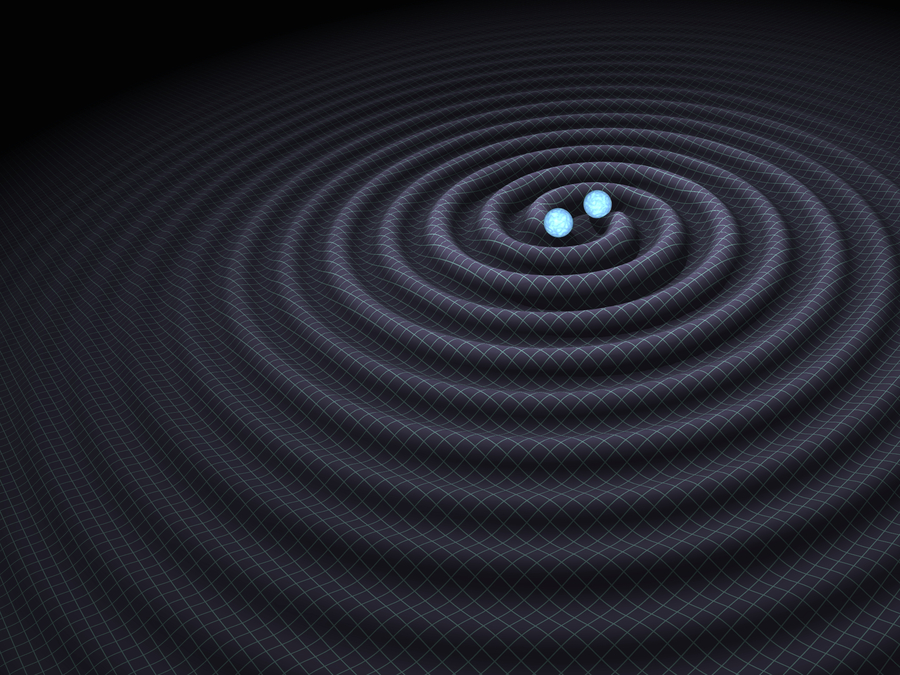

Gravitational Waves

Gravitational waves are tiny ripples in space created by accelerating masses such as the orbit of neutron stars and black holes. As a gravitational wave passes through space it changes the distance between two points. Researchers at Penn State study gravitational waves theoretically as well as observationally through the LIGO and Virgo observatories.

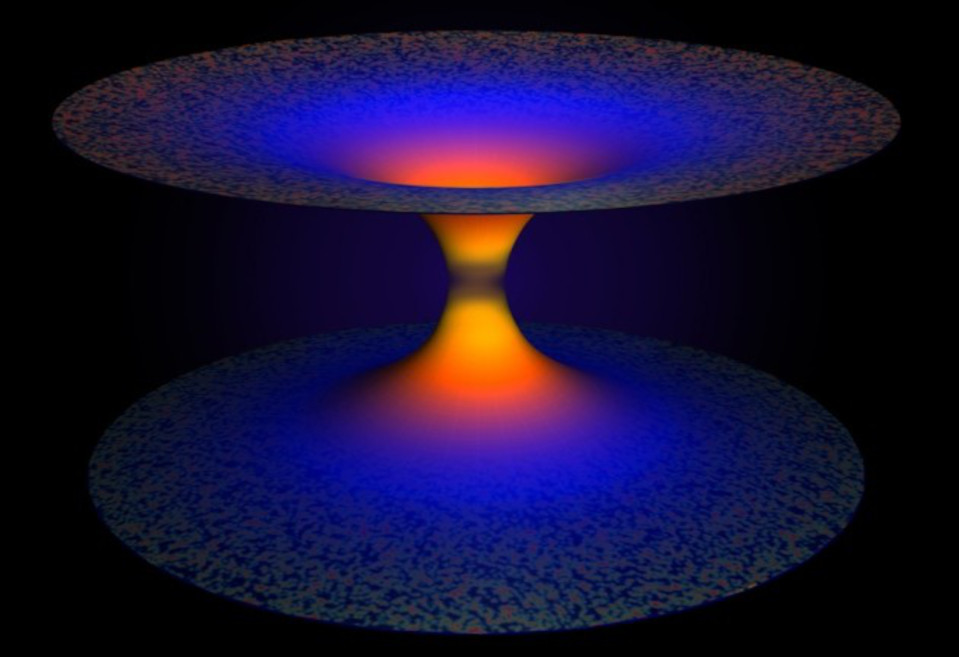

Loop Quantum Gravity

Loop Quantum Gravity is a theory of quantum gravity based on a geometric formulation that predict discrete geometrical phenomena above some minimum length scale (the Planck length).

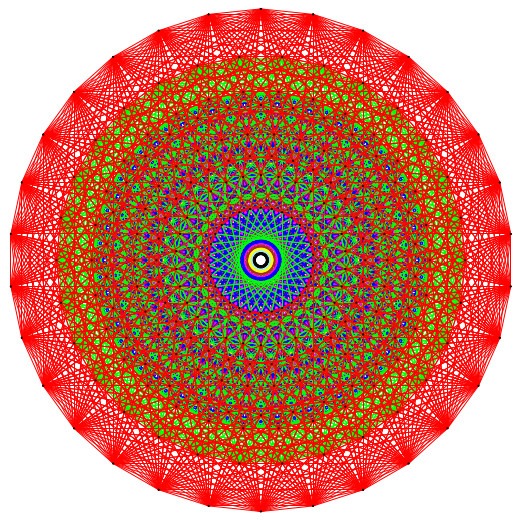

Mathematical Structures

Physics often advances when crisp mathematical structures are uncovered in a framework developed to describe observed phenomena. For example, in quantum field theory there is a vast discrepancy between the current calculational difficulty in making predictions for experiments and the simple, mathematical form of the end result. The Amplitudes program seeks to explain and exploit this surprising simplicity by reformulating the basic mathematical tools used to make predictions.

Multimessenger Astrophysics

Many astrophysical phenomena release not just light (electromagnetic radiation), but also gravitational waves and/or elementary particles including neutrinos and cosmic rays. Each of those signals carries different information about the physics of the source, so collecting more than one enables us to have a deeper understanding of the event that produced them. However, it is an enormous challenge for different types of instruments to coordinate simultaneous observations, and to verify that signals have a common source. Projects like AMON and SciMMA help alert the community to potential multi-messenger events so that an observing program can be coordinated as quickly and efficiently as possible.

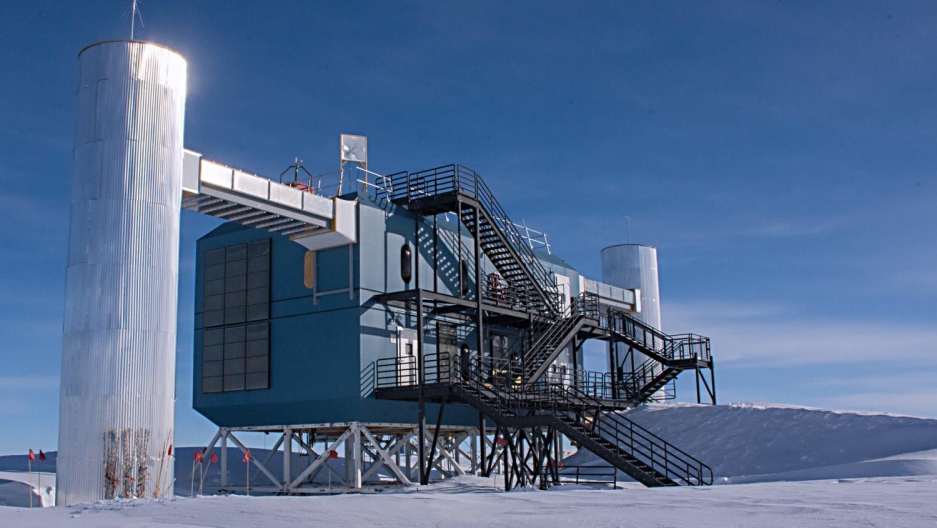

Neutrinos

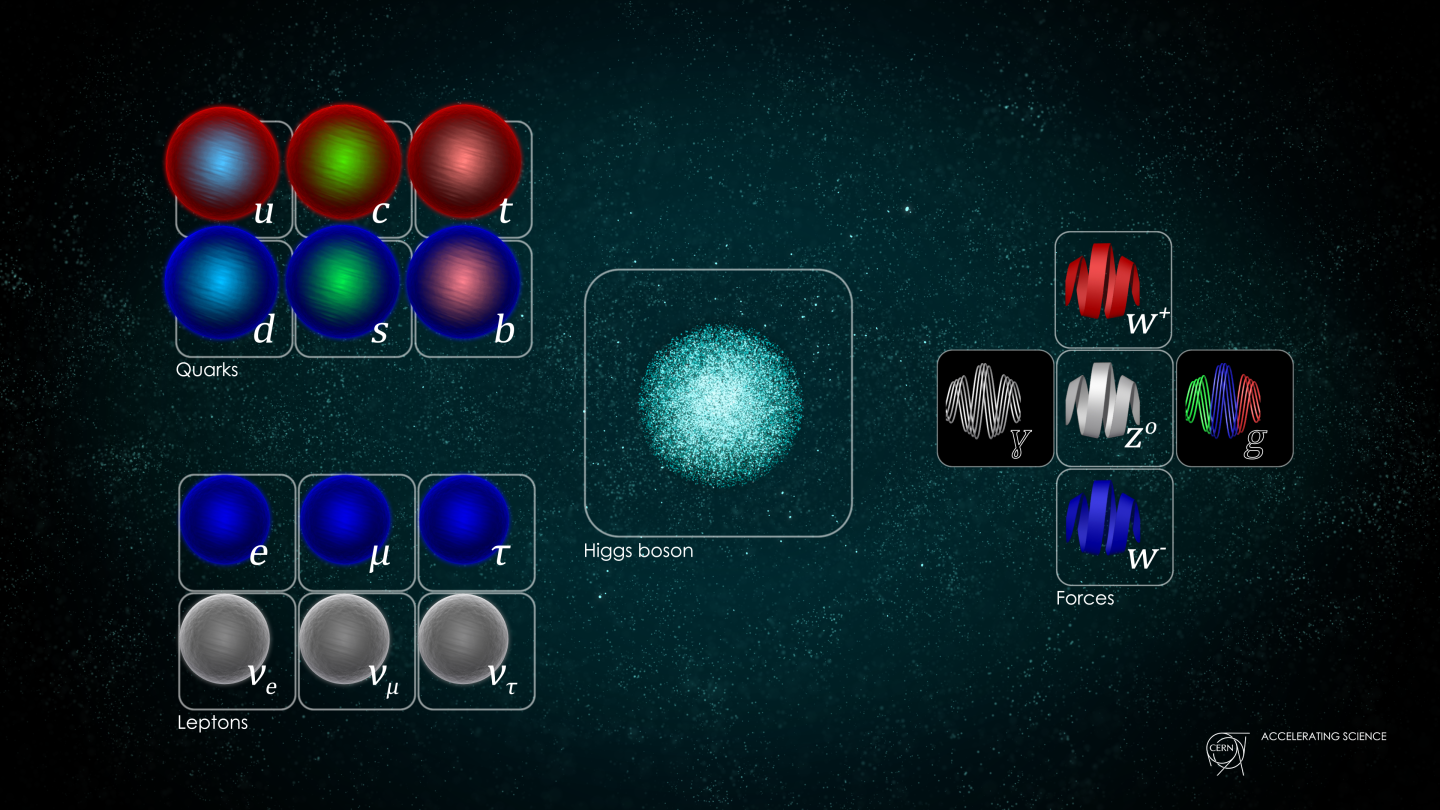

Neutrinos are light, electrically-neutral elementary particles that make up the least-understood part of the Standard Model of particle physics. Facilities like DUNE (the Deep Underground Neutrino Experiment) study neutrinos produced in the Fermilab collider as well as neutrinos arriving from cosmic events. Project 8 will measure neutrino mass by looking at neutrinos emitted when tritium decays. The CMB Stage 4 telescopes will use cosmological data to constrain the number of neutrinos and their mass. Many other neutrino facilities focus on detecting neutrinos produced in astrophysical processes, including ANITA, ARA, BEACON, GRAND, IceCube, PUEO, and RNO-G. These cosmic neutrinos can carry key information, along with electromagnetic radiation and gravitational waves, in "multi-messenger" detections of dynamic events in the universe.

Physical Mathematics

Physical mathematics is concerned with mathematics motivated by physics. Prime example of physical mathematics is the pioneering work of Eugene Wigner on the unitary representations of Poincare group which was motivated by his results proving that symmetries of quantum systems must be realized unitarily on their Hilbert spaces. His work opened up the huge field studying the unitary duals of noncompact Lie groups which is still an unfinished chapter of mathematics. In a similar vein, the discovery of supersymmetry by physicists led to the development of the theory of unitary representations of Lie superalgebras. Remarkably, though algebraically more complicated the theory of unitary representations of noncompact Lie superalgebras turned out to be simpler than those of noncompact Lie groups. Furthermore, some of the earliest results on AdS/CFT dualities were obtained, in a true Wignerian sense, within the framework of work on fitting the spectra of Kaluza-Klein supergravities into unitary supermultiplets of their underlying supersymmetry algebras.

Quantum Universe

All physical systems obey the laws of quantum mechanics, but we have not yet achieved a full understanding of the relationship between quantum mechanics, general relativity, and cosmology. The primordial universe and black holes are two arenas to study these questions in ways that are complementary to research on laboratory quantum systems and quantum information.

The strong force

The strong force out-competes the electromagnetic force on short distances to hold protons together in atomic nuclei. Nuclear matter can be studied in particle colliders and astrophysical objects like neutron stars. The quantum effects of particles that feel the strong force are important for many measurements in particle physics, including the recently measured anomalous magnetic moment of the muon. Many theoretical predictions of the effects of the strong force rely on the numerically-intensive work that requires supercomputers.