Neutrinos

Neutrinos are light, electrically-neutral elementary particles that make up the least-understood part of the Standard Model of particle physics. Facilities like DUNE (the Deep Underground Neutrino Experiment) study neutrinos produced in the Fermilab collider as well as neutrinos arriving from cosmic events. Project 8 will measure neutrino mass by looking at neutrinos emitted when tritium decays. The CMB Stage 4 telescopes will use cosmological data to constrain the number of neutrinos and their mass. Many other neutrino facilities focus on detecting neutrinos produced in astrophysical processes, including ANITA, ARA, BEACON, GRAND, IceCube, PUEO, and RNO-G. These cosmic neutrinos can carry key information, along with electromagnetic radiation and gravitational waves, in "multi-messenger" detections of dynamic events in the universe.

IGC members who study Neutrinos

| Name | Role | Affiliation | Phone | Office Address | Affiliated Center(s) | Research Topics(s) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Julien Alfaro | Graduate Student | Physics | jpa5771@psu.edu | +1 814 865 7533 | 204 Osmond Laboratory | IGC, CMA | Multimessenger Astrophysics, Cosmic Rays, Neutrinos |

| Tyler Anderson | Faculty | Physics | tba109@psu.edu | +1 814 865 2013 | 212A Osmond Laboratory | CMA | Cosmic Rays, Dark Matter, Neutrinos, Multimessenger Astrophysics |

| Mukul Bhattacharya | Postdoc | Astronomy, Physics | mmb5946@psu.edu | -- | 320A Osmond Laboratory | CMA | Multimessenger Astrophysics, Gravitational Waves, Neutrinos, Cosmic Rays |

| Carlos Blanco | Faculty | Physics, ICDS | carlosblanco@psu.edu | +1 814 865 7533 | 303K Osmond Laboratory | CFT, CTOC, CMA, IGC | Dark Matter, Neutrinos, Multimessenger Astrophysics, Cosmic Rays |

| Carmen Carmona Benitez | Faculty | Physics | mzc267@psu.edu | +1 814 865 6476 | 320D Osmond Laboratory | CMA | Dark Matter, Neutrinos |

| Jose Carpio Dumler | Graduate Student | Physics | jac866@psu.edu | +1 814 865 7533 | -- NONE | CMA | Neutrinos, Multimessenger Astrophysics, Dark Matter |

| Douglas Cowen | Faculty | Physics | dfc13@psu.edu | +1 814 863 5943 | 303D Osmond Laboratory | CMA | Dynamic Universe, Neutrinos, Multimessenger Astrophysics |

| Abhishek Das | Graduate Student | ICDS, Physics, Astronomy | ajd6518@psu.edu | -- | 321E Thomas Building | IGC, CMA | Cosmic Rays, Black Holes, Neutrinos, Gravitational Waves, Multimessenger Astrophysics, Dark Matter, Quasars |

| Luiz de Viveiros | Faculty | Physics | lad57@psu.edu | +1 814 865 7533 | 320E Osmond Laboratory | CMA | Neutrinos, Dark Matter |

| Kayla DeHolton | Postdoc | Physics | kld5938@psu.edu | -- | 303A Osmond Laboratory | CMA | Neutrinos |

| Derek Fox | Faculty | Astronomy | dbf11@psu.edu | +1 814 863 4989 | 425 Davey Laboratory | CMA, CTOC | Dynamic Universe, Neutrinos, Multimessenger Astrophysics |

| Reagen Garcia | Graduate Student | Physics | rgarcia@psu.edu | --- | 114 Osmond Laboratory | CMA | Neutrinos |

| Eduardo Gutiérrez | Postdoc | Physics | exg5366@psu.edu | +1 814 863 9605 | 301B Whitmore Laboratory | IGC | Black Holes, Multimessenger Astrophysics, Neutrinos, Gravitational Waves, Cosmic Rays |

| Peter Hammond | Postdoc | Physics | pph5189@psu.edu | +1 814 863 9605 | 307 Whitmore Laboratory | IGC | Neutrinos, Gravitational Waves, Multimessenger Astrophysics |

| Bryan Hendricks | Graduate Student | Physics | blh5615@psu.edu | 815-216-0835 | 204 Osmond Laboratory | IGC | Neutrinos |

| Ali Kheirandish | Graduate Student | Physics | abk5717@psu.edu | +1 814 865 7533 | -- Davey Laboratory | CMA | Neutrinos, Multimessenger Astrophysics, Dark Matter |

| Ryan Krebs | Graduate Student | Physics | rjk5416@psu.edu | (814) 865-7533 | 322 Osmond Laboratory | CMA, IGC | Neutrinos, Multimessenger Astrophysics |

| Yuchieh Ku | Graduate Student | Physics | yuchieh@psu.edu | 8148628153 | 204 Osmond Laboratory | IGC | Neutrinos |

| Irina Mocioiu | Faculty | Physics | ium4@psu.edu | +1 814 865 3721 | 320G Osmond Laboratory | CMA | Neutrinos |

| Richard Mueller | Graduate Student | Physics | rjm6826@psu.edu | +1 814 865 7533 | 6E Osmond Laboratory | IGC | Neutrinos |

| Mainak Mukhopadhyay | Postdoc | Physics, Astronomy | mkm7190@psu.edu | -- | 320L Osmond Laboratory | CMA | Gravitational Waves, Neutrinos, Multimessenger Astrophysics |

| Kohta Murase | Faculty | Physics, Astronomy | kum26@psu.edu | +1 814 863 9594 | 321B Osmond Laboratory | CMA | Cosmic Rays, Neutrinos, Multimessenger Astrophysics, Gravitational Waves, Dark Matter |

| Peter Mészáros | Faculty | Physics, Astronomy | nnp@psu.edu | 814-863-4167 | 504 Davey Laboratory | CMA | Gravitational Waves, Neutrinos, Multimessenger Astrophysics |

| Surendra Padamata | Graduate Student | Physics | ssp5361@psu.edu | -- | 322 Osmond Laboratory | CMA | Multimessenger Astrophysics, Black Holes, Cosmic Rays, Gravitational Waves, Neutrinos |

| Yi Qiu | Graduate Student | Physics | yiqiu@psu.edu | 8142328268 | 322 Whitmore Laboratory | IGC | Black Holes, Neutrinos, Gravitational Waves, Multimessenger Astrophysics |

| David Radice | Faculty | Astronomy, Physics | dur566@psu.edu | +1 814 865 7533 | 304 Whitmore Laboratory | CMA | Black Holes, Neutrinos, Multimessenger Astrophysics, Gravitational Waves |

| Steinn Sigurdsson | Faculty | Astronomy | sxs540@psu.edu | +1 814 863 6038 | 426 Davey Laboratory | CMA | Neutrinos, Black Holes, Multimessenger Astrophysics |

| James Tutt | Faculty | Astronomy | jht12@psu.edu | +1 814 865 6338 | 128A Davey Laboratory | IGC | Neutrinos |

| Stephanie Wissel | Faculty | Astronomy, Physics | wissel@psu.edu | +1 814 863 9598 | 303B Osmond Laboratory | CTOC, CFT, CMA | Multimessenger Astrophysics, Cosmic Rays, Neutrinos |

| Chengchao Yuan | Graduate Student | Physics | cxy52@psu.edu | +1 814 865 0153 | -- NONE | CMA | Neutrinos, Multimessenger Astrophysics, Cosmic Rays |

| Andrew Zeolla | Graduate Student | Physics | avz5228@psu.edu | 7138709006 | 204 Osmond Laboratory | CMA | Multimessenger Astrophysics, Neutrinos, Cosmic Rays |

| Andrew Ziegler | Graduate Student | Physics | ziegler@psu.edu | -- | 6E Osmond Laboratory | CMA | Neutrinos |

News about Neutrinos

International team awarded $16.3M to fund neutrino detection

2025-12-08

Penn State Associate Professor Stephanie Wissel will design, construct specialized equipment to detect rare, high-energy particles Katie Yan 8 December 2025

Stephanie Wissel, associate professor of physics and of astronomy and astrophysics in the Penn State Eberly College of Science, is part of an international research team that was awarded a 14 million euros — equivalent to $16.3 million — European Research Council (ERC) Synergy Grant to support a multi-institutional collaboration focused on detecting rare neutrinos. These ultra-high-energy subatomic particles are emitted by high-energy sources in the universe, like supernovae or the environments around black holes, but neutrinos have no charge and are nearly massless, making them incredibly difficult to find. A portion of the grant will fund Wissel’s work on building a phased array, an assortment of antennas that digitally form beams to enhance the signal from neutrinos, at Penn State.

Wissel, who directs the Center for Multimessenger Astrophysics in the Penn State Institute for Gravitation and the Cosmos, is the only co-primary investigator based in a non-European Union country on the project, titled “Opening a new window on the violent Universe with the Hybrid Elevated Radio Observatory for Neutrinos (HERON).” The award is shared among Wissel and three other co-primary investigators and their respective institutions: Kumiko Kotera, who serves as the coordinator the project, from the Institut d’Astrophysique de Paris in the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifque in France; Olivier Martineau from the Université Sorbonne in France; and Jaime Álvarez-Muñiz from the Universidade de Santiago de Compostela in Spain. The team is also working with Federico Sanchez from the Comisión Nacional de Energía Atómica, in Argentina. Their project was one of 66 awarded out of 712 proposals.

“HERON is an ambitious project where we have a shot at discovering the most energetic neutrinos,” Wissel said. “Since neutrinos rarely interact with matter, they can travel across the universe unimpeded and they can probe the deep inner workings of dense and violent environments like massive stellar explosions, jets driven by black holes and more.”

To detect neutrinos, highly specialized equipment is needed. The HERON project’s goal is to build a new observatory atop the mountains of San Juan province in Argentina. A network of antennas distributed along nearly 45 miles of the mountainous region will observe the radio flashes that neutrinos can produce when they impact the Earth’s crust. HERON will also connect to the global multi-messenger network — a system of observatories that look for different types of cosmic signals allowing events detected by one to be followed up by others — responding to and sending alerts of possible neutrino emitters like gamma ray bursts, active galaxies and other high-energy cosmic events.

There are two components to the HERON telescope: the phased array Wissel is leading and a standalone antenna array that improves the telescope’s ability to figure out where the neutrino came from.

HERON will combine the approaches of two previous projects, both of which are concepts for large-scale neutrino detectors that can also detect cosmic rays: BEACON and GRAND. Wissel and her team demonstrated that they could deploy phased arrays on an elevated mountain surface with a prototype for BEACON at the White Mountain Research Center in California. GRAND, the second project, showed that an extended network of autonomous radio antennas could detect cosmic rays, which are more prevalent than neutrinos and provide proof-of-concept for the experimental approach. The combination of these two technologies — the phased system and the ability to reconstruct neutrinos with high precision and reject background noise with antennas separated by long distances through the standalone array — aim to increase neutrino detection and identification.

“My understanding is that neutrinos are the second most abundant form of matter in the universe, surpassed only by photons,” said Aleksandra Slavković, associate dean for research in the Eberly College of Science. “This project brings to Penn State an exciting international collaboration in which Stephanie and her team are leading the development and implementation of a critical component of the HERON instrument. HERON will be one of the most sensitive instruments in the world for detecting ultra-high-energy neutrinos — potentially enabling their first direct observation. It is an extraordinary scientific opportunity; one aligned with discoveries of Nobel-level significance.”

Click here for the full article.

Additional links:

What happens when neutron stars collide?

2024-06-18

When stars collapse, they can leave behind incredibly dense but relatively small and cold remnants called neutron stars. If two stars collapse in close proximity, the leftover binary neutron stars spiral in and eventually collide, and the interface where the two stars begin merging becomes incredibly hot. New simulations of these events show hot neutrinos — tiny, essentially massless particles that rarely interact with other matter — that are created during the collision can be briefly trapped at these interfaces and remain out of equilibrium with the cold cores of the merging stars for 2 to 3 milliseconds. During this time, the simulations show that the neutrinos can weakly interact with the matter of the stars, helping to drive the particles back toward equilibrium — and lending new insight into the physics of these powerful events.

Click here for the full article.

Additional links:

IceCube identifies seven astrophysical tau neutrino candidates.

2024-03-12

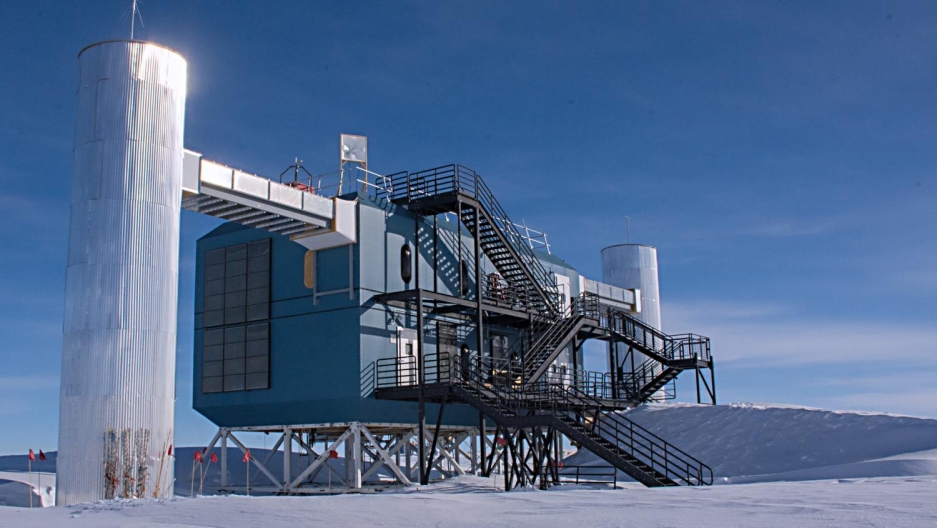

The IceCube Neutrino Observatory, a cubic-kilometer-sized neutrino telescope at the South Pole, has observed a new kind of astrophysical messenger. In a new study recently accepted for publication as an Editors' Suggestion by the journal Physical Review Letters and available online as a preprint, the IceCube collaboration, including Penn State researchers, presented the discovery of seven of the once-elusive astrophysical tau neutrinos.

Click here for the full article.

Additional links:

IceCube Observatory Produces First Image of the Milky Way using Neutrinos

2023-07-06

Our Milky Way galaxy is an awe-inspiring feature of the night sky, viewable with the naked eye as a horizon-to-horizon hazy band of stars. Now, for the first time, the IceCube Neutrino Observatory has produced an image of the Milky Way using neutrinos — tiny, ghostlike astronomical messengers that are extremely difficult to detect because they rarely interact with matter. In an article published online today (June 29), in the journal Science, the IceCube Collaboration, an international group of over 350 scientists, including Penn State researchers, presents evidence of high-energy neutrino emission from the Milky Way.

“Most of what we know about our universe and our host galaxy we have learned by observing electromagnetic radiation — this includes visible light but stretches in energy from radio waves to x-rays and gamma rays,” said Doug Cowen, professor of physics in the Penn State Eberly College of Science and a member of the IceCube Collaboration. “This new image of the Milky Way using neutrinos is completely different and allows us to explore questions about the origins and workings of our galaxy in new ways.”

The high-energy neutrinos, with energies millions to billions of times higher than those produced by the fusion reactions that power stars, were detected by the IceCube Neutrino Observatory, a gigaton detector operating at the Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station. It was built and is operated with National Science Foundation (NSF) funding and additional support from the 14 countries that host institutional members of the IceCube Collaboration. This one-of-a-kind detector encompasses a cubic kilometer of deep Antarctic ice instrumented with over 5,000 light sensors. IceCube searches for signs of high-energy neutrinos originating from our galaxy and beyond, out to the farthest reaches of the universe. “As is so often the case, significant breakthroughs in science are enabled by advances in technology,” said Denise Caldwell, director of NSF’s Physics Division. “The capabilities by the highly sensitive IceCube detector, coupled with new data analysis tools, have given us an entirely new view of our galaxy — one that had only been hinted at before. As these capabilities continue to be refined, we can look forward to watching this picture emerge with ever-increasing resolution, potentially revealing hidden features of our galaxy never before seen by humanity.”

Interactions between cosmic rays — high-energy protons and heavier nuclei, also produced in our galaxy–and galactic gas and dust inevitably produce both gamma rays and neutrinos. Given the observation of gamma rays from the galactic plane, the Milky Way was expected to be a source of high-energy neutrinos, according to the research team.

IceCube has previously detected energetic neutrinos from astrophysical sources at much greater remove than our own Milky Way galaxy, but those sources were situated in the northern sky, allowing analyzers to use the Earth as a filter to remove everything but neutrinos. Due to the orientation of the Earth in the Milky Way, many potential galactic sources of neutrinos are located in the southern sky.

“That means that analyzers had to devise other methods to reduce the background from particles raining down on the detector from cosmic-ray interactions in the atmosphere in the vicinity of the South Pole,” said Cowen. “Those particles would otherwise completely obscure the galactic neutrino signal.”

To overcome this background, IceCube collaborators at Drexel University developed analyses that select for “cascade” events, or neutrino interactions in the ice that result in localized, roughly spherical showers of light. Because the deposited energy from cascade events starts within the instrumented volume, contamination of atmospheric muons and neutrinos is reduced. Ultimately, the higher purity of the cascade events gave a better sensitivity to astrophysical neutrinos from the southern sky. However, the final breakthrough came from the implementation of machine learning methods, developed by IceCube collaborators at TU Dortmund University, that improve the identification of cascades produced by neutrinos as well as their direction and energy reconstruction. The observation of neutrinos from the Milky Way is a hallmark of the emerging critical value that machine learning provides in data analysis and event reconstruction in IceCube.

“The improved methods allowed us to retain over an order of magnitude more neutrino events with better angular reconstruction, resulting in an analysis that is three times more sensitive than the previous search,” said IceCube member, TU Dortmund physics doctoral student and co-lead analyzer Mirco Hünnefeld.

The dataset used in the study included 60,000 neutrinos spanning 10 years of IceCube data, 30 times as many events as the selection used in a previous analysis of the galactic plane using cascade events. These neutrinos were compared to previously published prediction maps of locations in the sky where the galaxy was expected to shine in neutrinos.

The maps included one made from extrapolating Fermi Large Area Telescope gamma-ray observations of the Milky Way and two alternative maps identified as KRA-gamma by the group of theorists who produced them.

“This long-awaited detection of cosmic ray-interactions in the galaxy is also a wonderful example of what can be achieved when modern methods of knowledge discovery in machine learning are consistently applied,” said Wolfgang Rhode, professor of physics at TU Dortmund University, IceCube member and Hünnefeld’s adviser.

The power of machine learning offers great future potential, bringing other observations closer within reach.

Click here for the full article.

Additional links:

Icecube Neutrinos Give First Glimpse Into the Inner Depths of an Active Galaxy

2022-11-09

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. — For the first time, an international team including Penn State scientists has found evidence of high-energy neutrino emission from Messier 77, also known as NGC 1068, an active galaxy in the constellation of Cetus.

Neutrinos are fundamental particles with no charge and almost no mass, and they rarely interact with other matter. High-energy neutrinos — like those detected here with energies in the teraelectron volt (TeV), or trillion-electron volt, range — can travel for billions of light-years through space without being deflected or absorbed. Thus, while they are extremely difficult to detect, they can provide accurate information about the distant universe, especially when the information the carry can be combined with information from other cosmic signals in what is called “multimessenger” astronomy.

The detection was made by the IceCube Neutrino Observatory, a massive neutrino telescope encompassing one billion tons of instrumented ice at depths from 1.5 to 2.5 kilometers below Antarctica’s surface near the South Pole.

“IceCube is a veritable discovery machine,” said Doug Cowen, professor of physics and of astronomy and astrophysics at Penn State and a long-time IceCube collaborator. “The huge detector has lived up to its promise to launch the brand-new field of high energy neutrino astronomy, and then some, now by giving us glimpses behind a black hole’s black-out curtain of matter. IceCube has once again proved that when humanity points a new instrument at the heavens — starting with Galilleo’s first telescope — our knowledge of the universe around us increases by leaps and bounds.”

This unique telescope, which explores the farthest reaches of our universe using weakly interacting neutrinos instead of light, recorded the first observation of a potential source of high-energy astrophysical neutrinos in 2017. The source of these first observations is the known blazar TXS 0506+056, which is situated in the night sky just off the left shoulder of the constellation Orion and about 4 billion light-years from Earth.

Blazars are very luminous and distant active galaxies with a powerful, relativistic jet of particles pointing directly at us. Unlike NGC 1068, the blazar TXS 0506+056 had not been studied much before the multimessenger detection of neutrinos and high-energy electromagnetic radiation that allowed follow-up measurements by almost 20 telescopes around the world. Now, the observation of neutrino emission from a different type of active galaxy brings us closer to understanding the supermassive black holes powering them.

“One neutrino can single out a source. But only an observation with multiple neutrinos will reveal the obscured core of the most energetic cosmic objects,” said Francis Halzen, a professor of physics at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, the headquarters of the National Science Foundation (NSF)´s Antarctic neutrino facility, and principal investigator of IceCube. “IceCube has accumulated some 80 neutrinos of TeV energy from NGC 1068, which are not yet enough to answer all our questions, but they definitely are the next big step towards the realization of neutrino astronomy.”

The results appear Nov. 4 in the journal Science.

Click here for the full article.

Additional links: